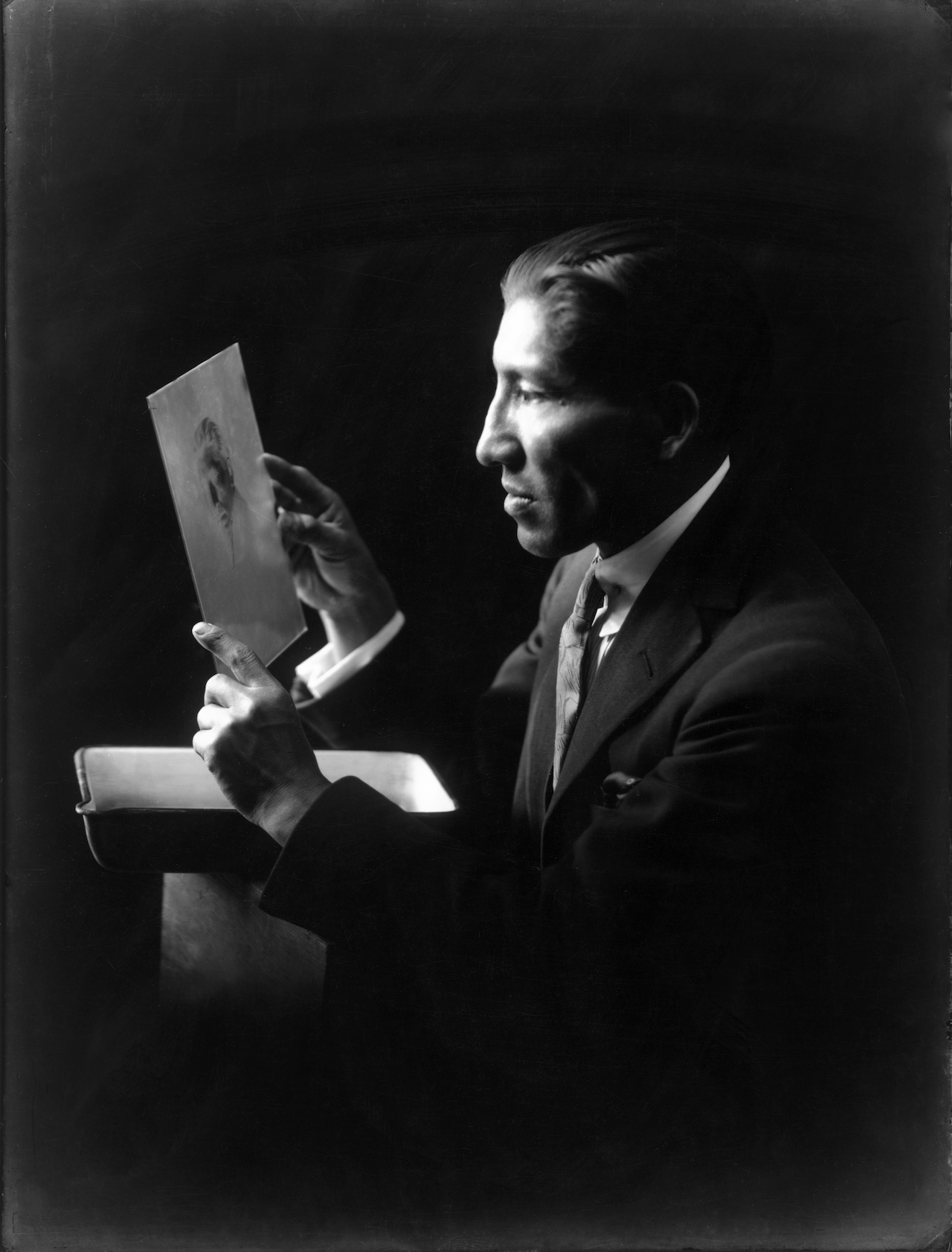

The Trailblazing Peruvian Photographer Who Captured a Vanishing World.

Tag Archives: photography

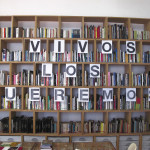

Photographic call for solidarity with victims of Iguala

Tlachinollan, Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña the Latinstock Foundation and Human Rights Organizations organizations in Latin America call for an international visual action in solidarity with the victims of kidnapping and murder that happened last September in Iguala, Estado de Guerrero, Mexico.

The visual campaign seeks photographers and groups of students who will pose for a picture with a sign reading in order to express world wide sympathy and support_for the missing students and their parents in their stuggle to pursue justice and truth for this brutal and unimaginable act of violence against unarmed young students. The sign reading will send a message for Truth and Justice to prevail in Mexico. The production of the sign should be made by the students so this becomes an educational experience in the production of images for a social and solidarity purpose.

The students and social organizations of Mexico will receive these images and distribute them around the country, in the social networks and in contact with the Mexican Human Rights Organizations such as Tlachinollan, that represents the families of the victims and other Photography and Human Rights organizations in Mexico. For them, this support is essential to strengthen their fight for justice and the respect for Human Rights, a struggle that will gain for them the support of sensible people around the world

The brutality against a group of 43 rural students of the Teachers Rural School Isidro Burgos of Ayotzinapa conducted by the Mexican state of Guerrero and its police in collusion with drug lords of that state , mark an elevated level of violence and horror exerted on Mexican people. This requires an immediate action in Mexico and around the world so that the truth is known and Mexicans can move ahead in the implementation of real justice in this case. World wide support as manifested in this campaign will give moral, public, and powerful support to the seekers of justice and truth in this case.

For more information, go to www.facebook.com/visualaction or to www.visualaction.org.

Apoyo/Support

- Andhes Asociacion de abogados de Tucuman http://andhes.org.ar/

- Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires/Universidad de Buenos Aires http://www.cnba.uba.ar/

- Centre de la Photographie, Genève, Suiza www.centrephotogeneve.ch

- Fotofest, Houston, USA www.fotofest.org/

- Estudio Madalena, Sao Paulo, Brasil estudiomadalena.com.br/

- Autograph, London, UK www. autograph-abp.co.uk

- Drik Picture Agency, Dhaka, Bangladesh www.drik.net

- Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Santiago de Chile www.museodelamemoria.cl/

- Parque de la Memoria, Buenos Aires, Argentina www.parquedelamemoria.org.ar

- Photograhic Museum of Humanity www.phmuseum.com

- Museo de la Memoria de Rosario, Argentina www.museodelamemoria.gob.ar

- Familiares de Desaparecidos y Detenidos por razones Politicas, Argentina www.desaparecidos.org/familiares/

- FAC Fundaciòn de Arte Contemporáneo, Montevideo, Uruguay facmvd.blogspot.com/

- Fundacion Infoto, Tucumàn, Argentina www.fundacion.infoto.com.ar

- EMAHO Magazine, India www.emahomagazine.com

- ECCHR European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, Berlin, Alemania www.ecchr.eu ,

- Lugar a dudas, Cali, Colombia www.lugaradudas.org

The images can be sent in low resolution to:

- tlachinollan.difusion@gmail.com

- almoca@prodigy.net.mx

- fundacion@latinstock.com

And in High Resolution, for possible exhibition in Mexico when the campaign is completed to: fundacion@latinstock.com

If your organization wants to join this initiative, please send an email and your URL to fundacion@latinstock.com

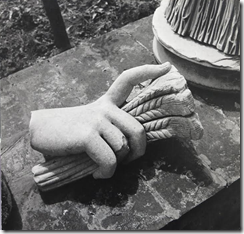

History under fire

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Therese Keogh was invited to create work for the Sievers Project, an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography that revisited the work of a major Australian photographer who documented the glories of industry in the 20th century. Keogh was drawn to Sievers’ photograph of a severed hand holding a sheaf of wheat, a fragment of the marble statue of Ceres in Rome. She discovered that much of the imperial marble was eventually transformed into quicklime used to make concrete. It can also be used as a soil amendment to counterbalance soil acidity. In order to investigate this process herself, Keogh sourced a marble pediment of an altar from a church in Ballarat. She then worked out how to fire this marble, which was eventually displayed in the gallery as a block of quicklime.

Keogh’s work witnesses the reduction of art into commerce. This can be seen as a loss echoing the demise of the grand paternalistic world of manufacture once celebrated by Sievers. But it can also be seen as a recovery of value from what is left behind, returning products of human endeavour to the earth from whence it came.

What is interesting from the perspective of South Ways is the adventure of the artist in confronting the material challenge herself, without recourse to external assistance. Her two hands thus provide a tangible link between the various phases of the cycle, moving from monument to earth. They allow us to witness the transformation of matter itself, a dimension otherwise absent from the silvery surfaces of Sievers’ prints.

Below are photos of the firing of the marble with Keogh’s description of the process:

These images show the firing of a marble object inside a large steel box. I started with a block of marble in my studio, and – over a period of several months – chipped away at its surface. I didn’t begin this process with an end point in mind. Part of me was looking for a fault in the marble, and so I kept carving in the hope that the stone would reveal its weaknesses, which would then allow me to stop. But one day the mallet I had been using broke with the force and repetition of the carving. The mallet’s head split in two, and it was like the marble was reacting against its own transformation. So I stopped.

Marble is a form of calcium carbonate, metamorphosed from limestone. When fired, the carbon dioxide trapped inside is burned away, transforming the calcium carbonate into calcium oxide, or quicklime. Quicklime doesn’t occur without human intervention, and is used for a variety of applications (including as a base ingredient in concrete, and, in agriculture, as a soil amendment to neutralise earth with high acidity). It is called quicklime (from the original meaning of the word ‘quick’ as something that is alive, or living) because when it comes into contact with water a chemical reaction takes place that creates extremely high temperatures, and has been known to cause severe burns to the skin of people working with it.

Once the carving had finished, I constructed a steel box that would house the marble during its firing. The box protected the marble from the smoke of the fire, and allowed it to be heated more evenly.

My mum owns a property in Central Victoria, where I took the marble and the box to be fired. I propped up the box, with the marble inside, on four bricks in a paddock, and built a fire around it. The fire burned for about eighteen hours, as I stoked it through the night. When it had died down, I took the lid off the box. The marble – now quicklime – had cracked as it heated and cooled. Its surface had changed from being luminous to kind of chalky, as its chemical composition was irreversibly altered from the fire.

Therese Keogh, After Firing (CaO), image courtesy Christian Capurro, 2014

Therese Keogh is a Melbourne artist – www.theresekeogh.com. Featured image at the top of this page is her hand-drawn version of the original Sievers’ photo.